“Lest We Forget”

By Jerry Hartman, Foundation President

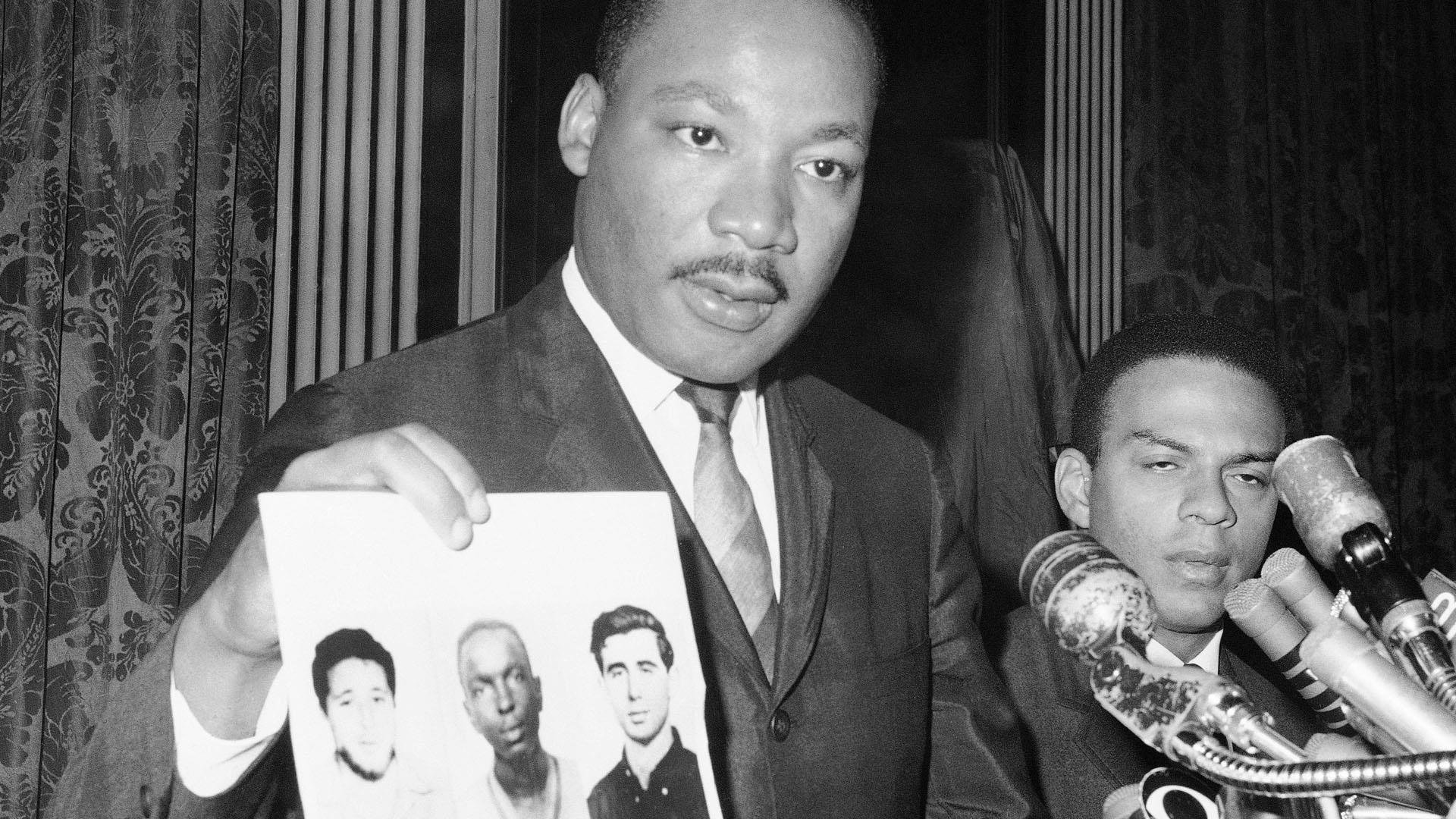

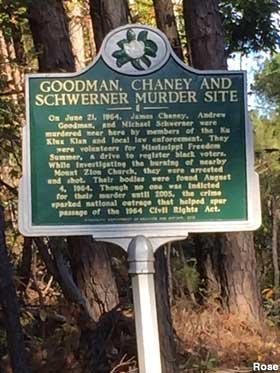

This month’s May issue of The Atlantic magazine contains an article, "Tour Guide to Tragedy," by Ko Bragg about his stepdad being an informal tour guide in Philadelphia, Mississippi to the historical events surrounding the murders there of three civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner by the members of the Ku Klux Klan in June 1964.

The article recounts the irregularity of these tours which could be found only by word of mouth in a town, Bragg writes, where officials, including the local museum, are still reluctant to tell that story. Hundreds of northern volunteers in an effort by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), as part of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), along with local civil rights activists, had joined forces that summer to register Black Mississippians to vote. Local citizens, says Bragg, don’t talk about the murders.

Eight years after those murders, I, with my then wife, Carolee Brady—born in Mississippi but educated at Columbia (Barnard College) in New York City—and Frances Green (now deceased), a law clerk that year to Judge Frank Johnson, decided to visit Philadelphia that fall of 1972 to see where the infamous events associated with those murders occurred, including the site of their burials in a dam for a farm pond.

Judge Johnson, a well-respected and revered Alabama federal trial judge, who was often himself the recipient of death threats, had single-handedly been responsible by his decisions for much of the desegregation of that State.

I was living in Ackerman, Mississippi that year clerking for James Coleman, a Judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Green and I had gone to law school together at George Washington University. Our trip occurred eight years after the signing by President Lyndon Johnson in July of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the watershed statute guaranteeing civil rights in virtually all aspects of American life. The outrage in America over the three killings had been a major impetus to Congress’ passage of that law. The Federal Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which included Alabama, had been the principal federal court of appeals responsible up to the time of our trip for many of the leading decisions carrying out the dictates of that statute.

All three of us thought that this trip would be an opportunity to become acquainted, observe, and learn about Mississippi, which we knew very little. The trip was joyful fueled by beautiful weather, the sights of rural life, and discussions we had with people along the way, especially Black Americans who, in response to our questions, recounted their stories about growing up and living in Mississippi.

When we reached Neshoba County, where Philadelphia is located, we headed to find the gravesites at the dam where the three civil rights workers had been buried. I truly can’t say after these many years what motivated us then to go straight there.

It was a pilgrimage to remember an event that had burned in our collective memories—a thought that we had all shared during that drive.

When we reached in a very rural area what we thought was the earthen dam, we were pulled over for no reason by the Mississippi Highway Patrol. Petrified, all three of us feared we would suffer the same fate as the slain civil rights workers. Asked to get out of my 1965 black Oldsmobile, the three of stood with our backs to the car. The two, large of stature, white patrolmen, wearing those wide-brimmed hats, initially said very little as they looked inside our car and then in its trunk.

We knew that they were hoping to find pot as a basis to arrest us. We were clean. The expected question then came from one of them, “what are the three of you doing here?” I spoke. I knew for sure that if I told the truth and said who we were and what we were doing, we might end up dead.

“We were looking for the famous Neshoba County Fair Grounds,” which I knew from reading the map to get there was nearby, “and we must have gotten lost.” How I came up with that story, I still have no idea, but it worked. Perhaps the fact that there were two females with me might have also helped. After showing identifications, that included my Mississippi driver’s license, and answering questions to which we all boldly lied, we were told to drive out of Neshoba County without stopping and not come back. I followed those instructions, all the while I looked in my rearview mirror to see if we were being followed.

Somewhat ironically, I returned to Mississippi in 1977 as an attorney in the United States Justice Department Civil Rights Division. Over the next four years, I tried numerous civil rights cases on assignments in Mississippi and Alabama, including one before Judge Johnson, with those twenty minutes of fear in Neshoba County under the scrutiny of two members of the Mississippi Highway Patrol never forgotten.

Copyright © 2022 Gerald Hartman