Justice O’Connor and Barbara McDowell: Common Themes

By Jerry Hartman, Foundation President and Board Chair

Barbara McDowell and Justice White

Barbara McDowell[1] met Justice O’Connor initially when she began clerking for Justice White in 1987. At that time, Justice O’Connor had been a Justice for six years. They shared a somewhat common experience. Justice O’Connor would often say that when she graduated from Stanford Law School at the top of her class in 1952 (third in her class of 102), she applied to numerous law firms and never received a job offer other than for a legal secretary position. At one job interview, she related that she was asked how well she typed.

Instead, she began her long career of public service by accepting a position as a deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California offering to work for no salary and sharing an office with a secretary, later remedied with a paid position. Thereafter, she worked for three years as a civilian attorney for the Army’s Quartermaster Corps in Germany where her husband was stationed after being drafted. They returned to Maricopa County, Arizona where Justice O’Connor took a five-year hiatus from law practice to begin raising a family and had three sons.

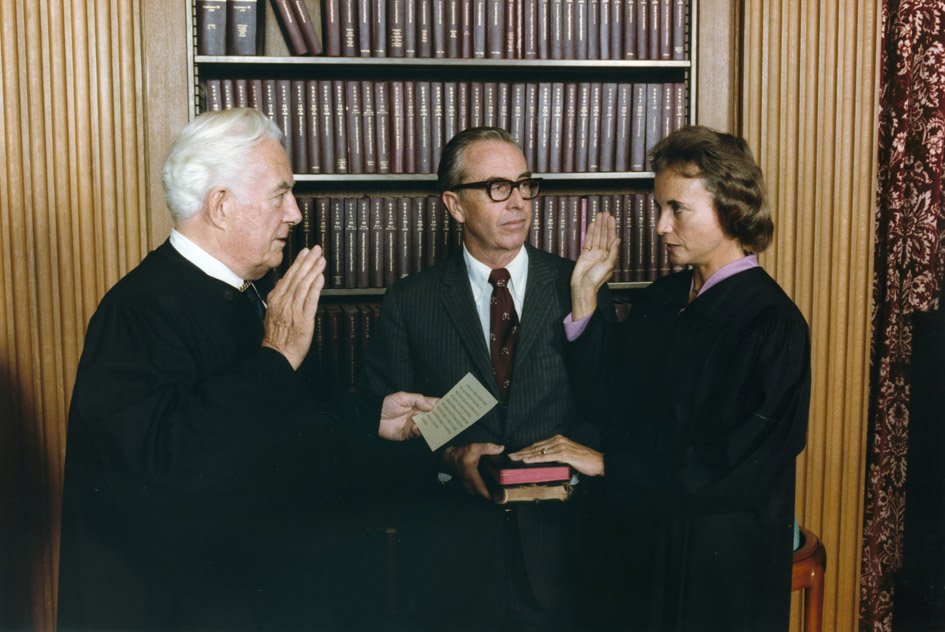

Justice O’Connor being sworn in by Chief Justice Warren Burger, her husband John O’Connor looks on

She then served as an Assistant Attorney General of Arizona from 1965 to 1969 that led to her being appointed by the governor to fill a vacant position in the Arizona State Senate when the incumbent left the position for a job in Washington. Justice O’Connor was later elected to that position in 1970 and became the first woman to serve as the State Senate Majority leader. Sequential positions in the Arizona court system (Maricopa County Superior Court Judge from 1974 to 1979 and Arizona State Court of Appeals from 1979 to 1981) preceded her appointment to the Supreme Court in 1981 by President Reagan.[2]

Barbara McDowell began her service as an Assistant[3] in the Solicitor General’s Office of the United States Justice Department in 1997 arguing cases in the Supreme Court on behalf of the United States where over the next seven years she argued 18 cases, including two on the same day, a feat very rarely occurring in the Court’s history.[4] One such case, Hillside Dairy Inc. v. Lyons, 539 U.S. 59 (2003), gave rise to an event that Barbara took much pleasure sharing. The case, a complicated challenge under the Commerce Clause by out-of-state dairy farmers to a California law taxing them with respect to milk production more than instate dairy farmers, required Barbara to share her argument time with an attorney in California for the instate producers who wanted the California law to be upheld.

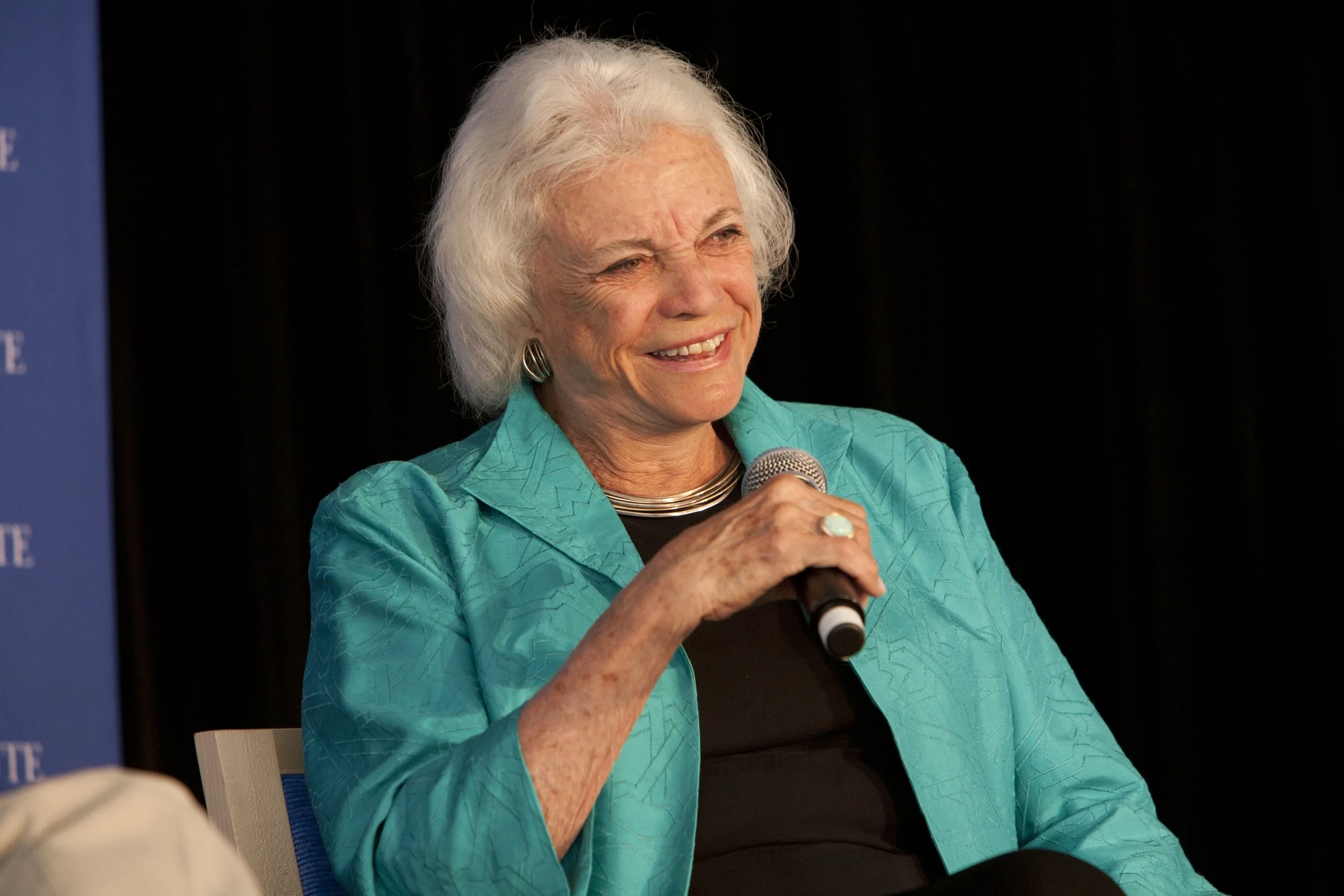

Justice O’Connor

It turned out that Barbara knew that California attorney from her time in college when she worked one summer as a legal secretary at his law firm. Barbara was appearing as an amicus for the United States supporting the instate producers. Under the Supreme Court’s rules, she had to share her argument time with this attorney. After identifying herself to him in a telephone call, relating the reason for contacting him about sharing her argument time, and stating that she had worked in college for his law firm, the attorney stated that it was wonderful that Barbara had made it to Washington to work in the Solicitor General’s office as a legal secretary. Barbara would tell that story with all the appropriate flourishes and pauses, concluding with that she allotted him the minimal argument time permissible. Barbara knew then of Justice O’Connor’s experience of being asked to work as a legal secretary upon graduation from Stanford Law School.

Barbara shared another experience with Justice O’Connor: one that flowed from their personal history steeped in their western roots. Justice O’Connor was born in El Paso, Texas on March 26, 1930. Her family had a 198,000-acre cattle ranch that stretched from southeastern Arizona to southwestern New Mexico. There were 2,000 cattle on the ranch. Her family lived in an adobe house that had no running water or electricity until she was seven.

Likewise, Barbara McDowell had western roots. Barbara’s mother, Joyce Benson, was born in Bemidji, Minnesota on October 18, 1923, and attended a one-room school until she went to high school. Her experience with firearms growing up was reflected in her having taught gunnery as a WAVE in the United States Navy during World War II. She later graduated from Fresno State University and taught in the Fresno public schools. Barbara attended public schools in Fresno.[5]

Her father, James McDowell, was born on March 1, 1924, in Glendive, Montana. He was a civil engineer and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, spending his entire career at the California Department of Highways. Barbara liked to point out that her maternal grandfather owned and ran a mink ranch in Northern Minnesota.

Barbara McDowell

During her time in the Solicitor General’s office, Barbara argued numerous Supreme Court cases where Justice O’Connor sat on the Court. One case, Minnesota v. Millle Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999), directly underscored their Western backgrounds. In that case, the State of Minnesota argued that the Chippewa Indians’ retention of their hunting, fishing, and gathering rights (usufructuary rights), which the Chippewas claimed was guaranteed to them in an 1837 Treaty, was abrogated by a Presidential Executive Order from 1850 that removed the tribe from the land located in Minnesota and Wisconsin where the Chippewa Indians exercised those rights. To prepare for her argument, Barbara traveled to Minnesota to meet with the Tribe at its request. She smoked a peace pipe by Leech Lake that bordered this land at dawn with leaders of the Tribe who had gathered there to pray for her success in her argument. Barbara jokingly wondered whether she could be arrested for smoking Peyote.

Barbara won in a 5 to 4 decision written by Justice O’Connor in a case no one expected her to prevail. Justices Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas dissented. Justice O’Connor in her decision separated the 1837 Treaty’s purpose providing for the purchase of that land by the United States in exchange for 20 annual payments of goods and money from the termination of those usufructuary rights which the Chippewas in the negotiations insisted on preserving. She held further that an 1850 Executive Order by President Taylor, which removed the Chippewas from that land and revoked their usufructuary rights, was ineffective to terminate the Chippewa’s usufructuary rights guaranteed under the 1837 Treaty because those rights existed independently of land ownership.

Likewise, Justice O’Connor applied that same reasoning to an 1855 Treaty stating that the Chippewas conveyed the land in question, but the Treaty’s language did not abrogate their usufructuary rights. Similarly, Justice O’Connor held that the Chippewas’ usufructuary rights were not extinguished when Minnesota was admitted to the Union because the Enabling Act admitting Minnesota made no mention of Indian treaty rights and no legislative history suggested otherwise. Justice O’Connor’s decision recounted in stirring fashion the treaty negotiations between the Chippewa Indian tribe and the United States government and the history surrounding those negotiations.

Barbara long felt that the decision in this case written by Justice O’Connor, over a strong dissent written by Justice Rehnquist preserving what she knew to the Chippewa Indians were their sacred Indian rights, was the greatest accomplishment of her legal career and the one that brought her the most satisfaction.

Barbara was keenly aware of mistreatment and removal of Native Americans from their tribal lands when she argued Minnesota v. Mille Lac Band of Chippewa Indians. That sad history, replete with Supreme Court decisions meshed in the United States’ exercise of its so-called “plenary power,” is recounted by Justice Kavanaugh in his concurrence in Haaland v. Brackkeen, 142 S. Ct. 1205 (2022) and the 2023 book by Ned Blackhawk, The Rediscovery of America (Native Peoples And The Unmaking of U.S. History). Justice Marshall in McClanahan v. Arizona State Tax Comm, 411 U.S. 164, 172 (1973) concisely framed this quest by Native Americans for their sovereignty: “It must always be remembered that the various Indian tribes were once independent and sovereign nations, and that their claims to sovereignty long pre-dates that of our government.”

[1] Barbara McDowell died on January 2, 2009, from a glioblastoma—brain cancer—while working at Legal Aid of the District of Columbia as head of its Appellate Advocacy Project which after her death was named in her honor. She had initiated that Project and gone to work at Legal Aid after leaving the Solicitor General’s Office. The author of this Perspective was married to Barbara McDowell in 2000. He founded the Barbara McDowell Foundation and the Barbara McDowell Public Interest Law Center.

[2] Justice O’Connor resigned from the Supreme Court on January 31, 2006, and died on December 1, 2023.

[3] Assistant was the official title given to attorneys serving under the Solicitor General rather than Assistant Solicitor Attorney General.

[4] There are no Supreme Court records indicating how often a lawyer argued two cases before the Supreme Court on the same day according to the Supreme Court’s Clerk Office. An article on the Oyez website by James M. Thunder, dated February 4, 2022, lists the number of times an attorney has argued before the Supreme Court but does not include any information about whether any attorney argued twice on the same day. (www.oyez.org)

[5] Barbara attended Fresno State University for two years. There, she headed the presidential campaign for Senator George McGovern of South Dakota for Fresno County, the only county that McGovern won in California. Her last two years of college were spent at George Washington University which she attended so she could be a legislative aide for Senator Alan Cranston from California. She was valedictorian of her college graduating class. All further demonstrating her western heritage.

Copyright © 2024 Gerald Hartman