Challenging Unconstitutional Conditions in Texas’ Youth Prisons

By Lone Star Justice Alliance

Opened in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Texas’s youth prisons were once known as “reform schools.” These large facilities were in rural areas far from the urban communities that most of the youth within their walls were arriving from and operated with little funding or oversight. It was believed at that time that incarcerating delinquent youths in rural areas removed them from bad influences and ensured public safety. However, these isolated facilities quickly became notorious for abuse and brutality.

After years of repeated scandals, the decision in Morales v. Turman, 383 F. Supp. 53 (1974) detailed the abusive practices at the state’s reform schools. Psychologists, social workers, and prison consultants visited the facilities, reviewed records, and interviewed staff and youths. The investigation revealed the excessive use of isolation, psychotropic drugs, punitive labor assignments, and exotic forms of corporal punishment. Investigators documented psychological abuses such as punishments for speaking Spanish, racial and sexual slurs, and the use of “punk dorms” where youth were locked together in rooms and instructed to fight each other.

In 1995, the Texas legislature passed the Juvenile Justice Reform Act, which expanded tough sentencing guidelines. The budget appropriated more than $200 million to construct new youth penal facilities but still located in rural areas.

In 2007, an investigation revealed extensive abuse within the Texas youth system, resulting in the abolition of the Texas Youth Commission and the 2011 creation of the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (“TJJD”), the closure of over half of the state’s youth prisons, a dramatic reduction in the juvenile inmate population, and a redirecting of some resources to local juvenile justice programs.

Thereafter, state and county officials shifted toward keeping more youth engaged in criminal behavior under local supervision, where research suggests they have the best outcomes.[i] With many youth diverted from the system entirely or held in local facilities, youth sent to TJJD are often the most difficult to manage because of severe mental health needs or violent behavior. Unfortunately, the result is that the demands on TJJD have grown increasingly severe, while their institutional capacity has continued to shrink as competitive pressures reduced the agency’s hiring capabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the issue into stark relief. As more and more agency employees were either stuck at home or resigned, TJJD was unable to maintain enough facility staff to comply with state and federal law.

Even well after pandemic restrictions had relaxed in Texas, TJJD had a 71% staff turnover rate in the 2021 fiscal year. In June of 2022, less than half of the agency’s officer positions were filled by active employees. In July, the agency was forced to halt all intake of new youth.[ii] By August, the waitlist of youth detained in local facilities ballooned to over 140, with some youth sitting in detention for more than three months. In the letter announcing the halt in intake, Executive Director Carter stated,

“The current risk is that the ongoing secure facility staffing issue will lead to an inability to even provide basic supervision for youth locked in their rooms. This could cause a significantly impaired ability to intervene in the increasing suicidal behaviors already occurring by youth struggling with the isolative impact of operational room confinement.”[iii]

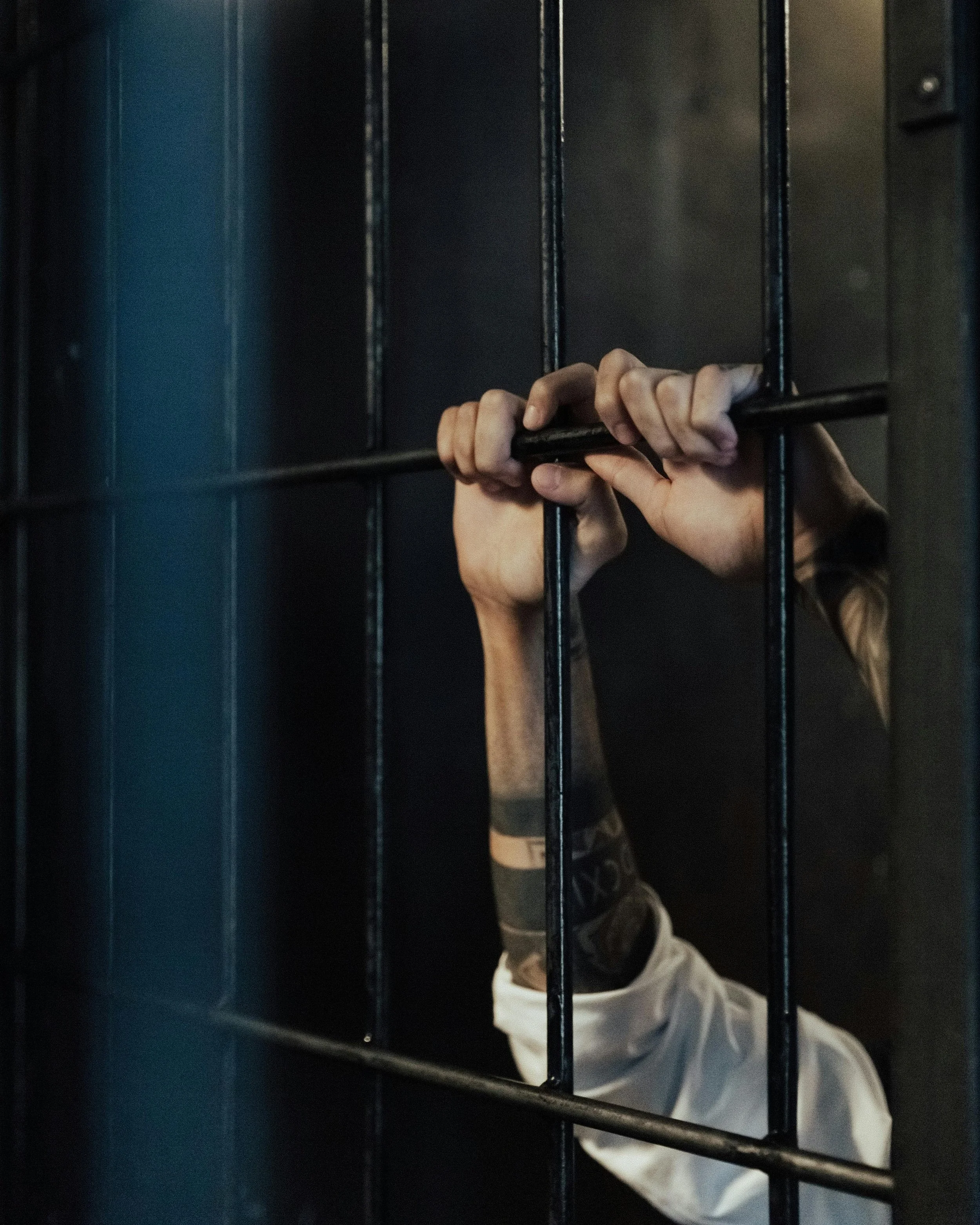

These employee shortages limited access to rehabilitative services and forced the agency to lock down dorms, only worsening the condition of the youth in TJJD’s care. At the peak of the crisis, hundreds of children were facing periods of isolation for as long as 23 hours at a time, locked in cells without any plumbing. Youth reported using their water bottles and lunch trays as makeshift toilets. Rehabilitative programming was almost entirely curtailed, and educational programming devolved to delivering packets of worksheets into the youths’ cells. Although the system’s total population dropped from an average of 842 in 2019 to 612 as of May 2022, the number of incidents of self-harm has almost doubled. TJJD data shows that in 2019, there were 1,181 incidents of self-harm in its facilities. That number rose to 1,761 incidents in 2020 and 2,104 in 2021.

Due to this extremely high level of risk in TJJD facilities, counselors spent roughly 30 hours a week solely on suicide risk assessments, resulting in far fewer hours to provide rehabilitative care. A report from the Texas Advisory Committee of the United States Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) found that chronic understaffing has led to “increased violence, unsanitary living conditions, and lack of basic health care and medical attention,” which may further traumatize detained children and exacerbate their mental health needs.[iv]

“Kids are self-harming to get out of their room… they are self-harming because they get to go to the clinic or the infirmary and have human contact.” Executive Director Carter said at the agency’s board meeting.

As the children’s condition deteriorated, the interactions between staff and youth became increasingly fraught and likely to result in an officer’s use of force. The USCCR report noted that officers physically restrained 2,947 youth between January and August 2020. In 2019, TJJD reported that staff used some variety of force against incarcerated children almost 7,000 times. Juvenile facility staff inappropriately use pepper spray to respond to behaviors that are manifestations of mental illness or developmental disabilities, even when staff are trained to use pepper spray as a last resort. TJJD reported a total of 2,960 deployments of pepper spray between September 2020 and August 2023. Across all facilities, nearly half (47%) of all youth were subjected to the use of force.[v] The increased incidence of violence and difficulty in managing the youth only exacerbated the pressures on staff retention.

The report also found that there was an increase in sexual misconduct investigations by the Office of Inspector General at four of TJJD’s facilities between 2020 and 2022, noting, “The instability in staffing levels decreases peer monitoring, which can increase opportunities for predatory staff to engage in abuse or exploitation.”[vi]

Additionally, chronic state-level issues divert the agency’s attention away from initiatives that would maximize diversion from state facilities, increase capacity at the local level, and encourage collaboration across county departments.

The Sunset Commission[1] review found that understaffing underscores “all other problems at TJJD, endangering youth and staff safety. More specifically, “chronic staffing shortages in state secure facilities affect nearly every aspect of committed youths’ lives and perpetuate TJJD’s problems with maintaining safety, providing treatment and services, and ensuring youths’ due process rights.”[vii] The legislature allocated additional funding during the 2022 legislative session[2] and TJJD introduced a 15% salary increase for Juvenile Corrections Officers, bringing them to parity with adult corrections officers. This has ameliorated some occasions of abuse, but conditions are far from stabilized, let alone to the point where youth confined in TJJD’s facilities have much hope of successful treatment and rehabilitation. During the summer of 2022, at the height of the staffing crisis, TJJD secure facilities functioned at roughly 200% of their capacity[3]; in September 2023, the agency still ran at 132% of capacity.[viii]

As recently as January 2024, Giddings State School was operating at 142% capacity.[ix] At the February 16th 2024 Board meeting, Executive Director Carter reported that the Giddings facility had spiked to 180% capacity, nearly returning to peak pandemic levels,

One approach to alleviating the chaos has been to shift more youth out of the ever-in-crisis juvenile prison system into the adult one. Lawmakers and prosecutors have promoted the idea to rid TJJD of its most disruptive and violent detainees.[x] However, TJJD is not just transferring the most dangerous youth, but also children with severe mental health needs who need the most help but react negatively to being restrained or verbally accosted by staff.

The adult prison system does not have age-appropriate care or supervision. This goes against the evidence-backed model of child-focused mental health care which prioritizes treating children as children and keeping them out of adult systems and prisons[4]. Rather than having a culture of rehabilitation, TJJD is preparing youth for transfer to adult prison. Without age-appropriate supervision and care, TJJD youth in adult systems are extremely vulnerable to abuse and increased self-harm.

An assault on a public servant that causes any bodily injury, no matter how serious, is at a minimum a third-degree felony, which carries a punishment of up to 10 years in prison.[xi] The legal standard for bodily injury is quite low, requiring only a showing that the complainant experienced pain. This low standard results in many youth acquiring additional felony charges, providing justification for their transfer to the adult system.

TJJD claimed that the eight youngest transfers in 2022, those who were age 16 at transfer, were responsible for 110 assault allegations against staff members. Lone Star Justice Alliance (“LSJA”) has seen a child charged with assault on a public servant when an officer tripped and hurt his knee while dragging a youth across the floor, or after an officer attempted to place a child in a restraint and sprained her wrist. These charges are at minimum third-degree and potentially second-degree felonies with decades of carceral consequences, applied to the conduct of a population of high-needs youth receiving nominal or no treatment amid a highly traumatic and dangerous environment.

Multiple studies show children incarcerated in adult facilities are significantly more likely to commit suicide than those housed in juvenile facilities.[xii] [xiii] The Texas’ adult prison system is well known for its severe conditions. TJJD’s current attitude to transfers drastically increases the likelihood that those youth with the most severe mental health challenges will be removed to an explicitly punitive and retributive setting.

Fundamental reforms are necessary. Texas must continue to shift resources away from high-capacity rural institutions and towards local diversion initiatives that have already demonstrated that they produce superior results.[xiv] These programs should be in populated areas, where employees with the requisite training for the difficult task of working with troubled youth can be sourced and paid a competitive wage. Diverting more low risk children from entering the justice system will free up space at the county level for the children currently held over capacity at TJJD. The current Texas model for juvenile incarceration is perpetually facing crises that transform Texas’ juvenile rehabilitative facilities into torture chambers.

Lone Star Justice Alliance (“LSJA”) is preparing to file a class action against the Texas Juvenile Justice Department to challenge the unconstitutional conditions of confinement for Texas youth. LSJA is pursuing legal remedies under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 8th Amendment and Prison Rape Elimination Act, among other appropriate remedies.

[1] Texas does not fund its agencies indefinitely, instead a state agency called the Sunset Advisory Commission evaluates the performance of individual agencies on a regular schedule. TJJD’s most recent Sunset review occurred in the midst of this crisis, providing additional insight into the goings on at the department as the legislature conducted their investigation.

[2] https://www.tpr.org/criminal-justice/2022-11-11/sunset-gives-roadmap-for-tjjd-but-removes-wage-increase-language-in-lieu-of-new-youth-prisons

[3] TJJD “capacity” measures are calculated by determining the number of staff required to meet state, federal, and agency standards for supervision, as well as needed staff to fill specialized roles, divided by the actual number of available staff. The calculation for the number of positions required varies with facility population.

[4] Neelum Arya, Getting to Zero: A 50-State Study of Strategies to Remove Youth from Adult Jails, UCLA School of Law, 2018. ; National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, “National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report” (2009). ; Campaign for Youth Justice, “Jailing Juveniles: The Dangers of Incarcerating Youth in Adult Jails in America“ (Nov. 2007).

[i] https://www.vera.org/news/diversion-programs-are-a-smart-sustainable-investment-in-public-safety%23:~:text=A%25202018%2520study%2520in%2520Harris,percent%2520over%2520the%2520same%2520period.

[ii] https://www.texastribune.org/2022/07/07/texas-juvenile-justice-staffing/

[iii]https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/86747ac4a73f8af26fcbfe3438328496/ShandraCarter-TempHold6-29-22.pdf

[iv] https://www.usccr.gov/files/2024-02/report-on-mental-healthcare-in-the-tjjd.pdf at page 21

[v] https://www.usccr.gov/files/2024-02/report-on-mental-healthcare-in-the-tjjd.pdf at page 12

[vi] https://www.usccr.gov/files/2024-02/report-on-mental-healthcare-in-the-tjjd.pdf

[vii] https://www.sunset.texas.gov/public/uploads/2023-08/TJJD%20and%20Office%20of%20the%20Independent%20Ombudsman%20Staff%20Report%20with%20Final%20Results_6-26-23.pdf

[viii] https://www.usccr.gov/files/2024-02/report-on-mental-healthcare-in-the-tjjd.pdf at page 13

[ix] JCO Strength Report 1-2-2024

[x] https://www.texastribune.org/2023/06/02/texas-youth-prison-crisis/

[xi] https://codes.findlaw.com/tx/penal-code/penal-sect-22-01/

[xii] https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/73555NCJRS.pdf

[xiii] https://eji.org/issues/children-in-prison/

[xiv] https://www.vera.org/news/diversion-programs-are-a-smart-sustainable-investment-in-public-safety%23:~:text=A%25202018%2520study%2520in%2520Harris,percent%2520over%2520the%2520same%2520period.